Little Eaton Schools

1. Introduction: Little Eaton in the 1800s

2. First formal school opened 1841

3. Life at the National School

4. Two Little Eaton School buildings: 1872 to 1884

5. The School Board and the new school 1880s

6. Headteachers and teachers from 1884 to 1945

7. School life in the early 1900s

8. Between the wars: life at school

9. The War Years

10. Post war to the present day

1. Introduction: Little Eaton in the 1800s

The 1800s were times of change for Little Eaton. The population increased from 395 in 1801 (80 houses) to 992 (209 houses) in 1901. In 1800, most employment was in agriculture, quarries or in trades such as blacksmiths or carpenters. Families kept allotments with chickens or a pig or cow. Most of the land in the parish was owned by the Dean of Lincoln, who owned a swathe of land to the north of the village; the Radford family owned Elms farm; and William Woollatt, brother-in-law of Jedidiah Strutt, owned land around the Outwoods. Most children were required to work from the age of six or seven and there were few adults who could read or write – most signed their name with an “x”.

But rapid change was afoot. Thomas Tempest was to convert Peckwash Mill from a corn mill into a Paper Mill, thereby making a fortune. The Bleach Mill on Mill Green took on more workers. The canal and gangway had arrived in 1795 so that stone from the quarries could be transported into Derby and beyond. Quarries at the Outwoods, Hierons Wood, Windy Lane and Moor Lane expanded. The New Inn was opened to add to the Queens Head (then called the Delvers), the King’s Head (now demolished) and the Anchor (now a private house). The Church had been re-built and consecrated in 1791. The demand for labour was high and new families were moving in. “Tittle Cock Fair” moved in at Easter, attracting thousands of visitors. Little Eaton was booming.

Against this background people in the village became aware of the need to provide education for the expanding child population. Until then, only a very few children received any formal education. There would be a governess at two or three bigger houses and older boys were sent to boarding school in Repton or elsewhere. The Church, and the Unitarian Chapel ran a Sunday school. There was a little private school, known as a Dames’ School, run by two ladies in a cottage next to the Church. More children began to have time for education as the “Factory Acts” in 1833, 1844 and 1847 limited the hours children were allowed to work. The Acts also required employers to make sure that children they employed received some education.

2. First formal school opened 1841

In 1841 Rev Richard Mellor paid William and Thomas Tempest 5 shillings so that ‘as a gift’ they ‘sell’ 170 square yards commonly called “Chapel Garden” – bounded to north and west by “Fields Lane” (now Vicarage Lane) and on the East by an orchard belonging to Jacob Wall – upon trust that “it was to be used as a school for the education of children of adults…of the labouring, manufacturing, or other poorer classes in the Township of Little Eaton” and as a residence for the school master. A building, now the Parish Rooms, was erected at a cost of £200. This was known as The National School. It had one main room in which were educated between 60 and 100 pupils. The Headteacher would take a class of older pupils, mainly 7 to 12 year-olds, at one end of the room and another teacher would take the younger ones. One or two 13 to 15 year old “Pupil teachers” were appointed to assist.

Here is the list of Headteachers of the school.

• 1841-1848: Rev. James Holmes

• 1848-1854: William Bland

• 1854-1865: Mr Tandy

• 1865-1866: Mr W Holland

• 1866: Joseph Pickard

• 1866-1879: Charles Taylor

Other teachers included:

• Mrs Frances Cocker (school mistress for over 20 years until she died in 1861)

• Miss Amelia Fanny Sudell, (born Lancs 1847) 1868 - Jan. “I became Mistress of Girls’ School”, she wrote in the Girls’ School Log Book which has unfortunately since disappeared. She left in about 1875 and became a teacher in Preston.

• Mrs Bamford - teacher in 1860s

• Sarah Hunt (aged 63 in 1861)

• Ann Stone (aged 65 in 1861)

Pupil Teachers

These were usually the brightest girls. But Thomas Bates at age 16 in 1860 was also appointed as a pupil teacher. Thomas was the eldest son of a local farmer. He later moved to London and became a rich man. In his Will he left several bequests to his native village, including money to buy land for St Peter’s Park. An obelisk was erected with a dedication to his teachers William Bland and Frances Cocker.

Another Pupil teacher was William Sharpe, born 1844. He lived with his parents and four siblings on Pooles Row. Living with them was another pupil teacher, Joseph Hurst, born in Breadsall in 1842. In 1862 when William was 18, the School Log book records that- “William Sharpe is compelled to return home from excessive internal weakness, which is accompanied by frequent spitting of blood”. Two months later Dr Taylor of Derby gives the following medical certificate- “This is to certify that Wm Sharpe has been under my care, suffering from disease of the lungs. I consider him of a weak constitution and not sufficiently strong to bear the duties of a pupil teacher”

Another pupil teacher was Ann Mary Hodgson, born in Lancashire to parents described as “Independent Gentleman and wife”. In 1861 she was also living with her family on Pooles Row but by 1871 she was a school mistress, aged 26, living as a lodger with the Salt family of farmers at Prestwood Farm, Kedleston.

The pupil teachers were occasionally given extra training after school hours.

Here are some details about the two teachers mentioned on the obelisk.

William Bland (born 1828) became Schoolmaster in 1848 aged 20. He was at Little Eaton for 6 years. He married Hannah Sims in 1850. They had 7 children. The eldest, John was born in Little Eaton in 1853. A daughter (Elsie) became the principal of a private school in the 1890s. He left in 1854 and became schoolmaster of William Gilbert Endowed school in Duffield where he taught for 40 years. On leaving Little Eaton, “the working classes” presented him with a bound copy of the National Encyclopaedia as “a mark of their approbation and esteem for the proper and efficient manner in which he discharges his duties as schoolmaster and for his earnest endeavours to promote their welfare”

Frances Cocker (born 1802) nee Burton. She married John Cocker (born 1806), a tailor in L.E. in 1830. They had 3 children, all of whom were at school when their mother was a teacher. The family lived on Eaton Bank, in one of the Blue Mountains Cottages. John Cocker died in 1860. By then Mrs Cocker (widow), still a National School Mistress, aged 60, is living with her married son William and his wife Elizabeth (a dressmaker) and their baby daughter. They are buried in the churchyard.

3. Life at the National School

Rev. Latham and his successors came in nearly every day to teach scripture. Older boys were taught map reading and book-keeping. Parents paid fees of 4 shillings per year = one penny (1d) per school week.

Later, needlework is mentioned as being taught to both boys and girls.

There are many examples in the School Log Book (written daily by the Headteacher) of children being sent home if their fees were not paid.

1866 “The Thompsons of the Blue Mountains do not meet their school payments as they should”

There was in addition a school grant, dependent on numbers of pupils attending, and if pupils arrived after the registers were closed they were not counted and were often sent home. In 1865 the Grant, based on average attendance was 11s 5d.

In these early days there was a high rate of truancy. Children were needed by parents for work, either at home or to earn a little extra money.

The Log Books report that the school was frequently closed because of fevers, bad weather, floods, so many children absent being needed for work, and occasionally for celebrations. There was an outbreak of scarlet fever in the village in 1868, resulting in very low attendance. Sometimes it was the illness of teachers that closed the school or resulted in classes being taught together in large groups.

1864: “serious and unexpected illness of the master” – boys and girls taught together for several months.

Children were also sent home for untidy appearance, being ‘dirty & smelly’, or ill.

Although Thomas Bates was a good scholar and a pupil teacher, it seems that his younger brothers, George and William, were not.

“George Bates too lazy to learn his verses.”

“George Bates sent home for repeated insubordination. His Mother afterwards came to the school and accused me of unkindness to her boy, which accusation I denied and challenged her to prove”

“William Bates must improve”

William became the village blacksmith in 1889.

The following are some more extracts from the Log Books, written by the Headteachers at the time (Mr Tandy and Mr Holland)

“Boys to Church on account of cattle plague” (?)

“Brought two girls into Boys’ School as punishment for their rudeness. Was disappointed in the effect which it produced.”

“I cautioned the boys against playing in the field opposite to the school. The bad example set by one of the teachers causing me to let the boys off without punishment”

“I was obliged to speak to R. Newsham about the very offensive smell caused by his dirty feet”

Eclipse of the sun 1867: “pleased the children”

“William Little drowned yesterday through playing truant, I commented upon it before the whole school showing them the consequences of disobedience and the uncertainty of human life”

“Several of the boys’ parents have requested me to excuse their children’s homework during the gardening time. I have consented”

1869 “Samuel Staton lost the key of the Schoolroom during the dinner hour and ran off home for fear of punishment”

Occasionally the Schoolmaster wrote “nothing of note occurred today”

Thomasing

Every year on Dec 21st, St Thomas’s Day, the Headteacher complains that the boys do not attend school due to the old custom of “Thomasing” – begging from house to house for provisions to get through the winter. The School Log Book in 1881 noted that there was only about half of the usual attendance “Owing to a custom of begging small doles” The Headteacher tried to tell the children how despicable the practice was but the children went anyway. One year only one pupil turned up at school.

John Latham and teacher training

A key figure of the period was the vicar, Reverend John Latham, vicar of Little Eaton church 1848 to 1878. He was a pioneer in establishing Derby College for School mistresses 1860, which provided a residential course for around 50 students. Several teachers at Little Eaton school were trained there, including Anne and Edith Poole (daughter of Joseph Poole the blacksmith and his brother Richard). Students paid a fee for their training and had to apply to Reverend Latham for a place on the course. Rev Latham died in 1878 so he did not see the opening of the new school on Alfreton Road.

4. Two Little Eaton School buildings: 1872 to 1884

Gladstone’s Education Act of 1870 spurred the Rev. John Latham and the Trustees to decide a Boys’ school should be built. The Church Commissioners donated some land in Barley Close. The building cost £300, paid for by public subscriptions of £193 plus a grant from the National Society.

The new School was opened in 1872. The Girls and Infants remained in the Parish Rooms. It only lasted 12 years, after which the school board – the church and some volunteers decided to build a new one.

The two school buildings were, in practice, run as a single organisation. Managing a school on two sites often proved difficult. There was a Headteacher who also taught in the senior boys’ building in Barley Close; and a “Mistress of the Girls” school, based in the Parish rooms with the girls and infants. Charles Taylor was Head between 1864 and 1879 and then Edwin Orford was appointed (at the age of 23) to take over. Alongside them Amelia Suddell was Mistress of the Girls until 1875, followed by Miss Gadsby between 1875 and 1884. For several months the Head’s brother, Arthur Orford, a third- year pupil teacher in a school near Stourbridge, on a visit (!) to Little Eaton taught the 2nd and 3rd Standards.

Inspection reports

There are reports of an Inspector’s visit to both buildings in the 1870s.

Girls School: “The attainment of children in the elementary subjects is still low. The present Mistress has not been long in charge and appears to be effecting some improvement. Some more books are required.”

Boys School: “The standard work was pretty fairly done, and half of those presented in grammar passed. The geography must improve. Some more books and maps are required.”

Edwin Orford was Headteacher between 1879 and1890, married to Emily Kate a schoolmistress. They had 3 children born in L.E. before moving to Sussex in 1890. Their son Edwin Lancelot was killed in action in France in 1915 aged 28. Here are some extracts from Mr Orford’s Log Book in the 1880s:

Miss Gadsby (Girls’ school) complaining about boys throwing stones at her school bell on their way home.

Mrs Littlewood called at school objecting to corporal punishment and home lessons for her two sons.

Punished several boys for lighting a fire in school playground during dinner hour. Dangerous - several thatched roofs and a hay rick.

Boys unable to bring school fees - fathers out of work because of frost and intense cold. V. small attendance, because of bad weather.

“After thawing a large (gallon) bottle of ink this afternoon and while carrying it to the cupboard, the bottom came out and the ink ran over the school floor.”

Another flood in village - v. poor attendance.

Admitted Henry Thums, aged 5, (John Easter’s Grandfather).

“It is with deep regret I have to state the death of William Birkinshaw, a scholar in the third Standard”

“Mrs Wheeldon came to school with a complaint respecting Alfred Robinson (Monitor) hitting her son Willie on the head. I therefore gave A.R. a reprimand as he is strictly forbidden to touch a scholar in any way whatsoever.”

“Mrs Fox brought Arthur Fox to school and requested me to punish him severely and keep him without his dinner for bad conduct at home. She declared him to be “quite uncontrollable during his father’s illness”. I declined to administer corporal punishment for home offences but kept him in all the dinner hour” (without dinner?)

Jan 11th Sent Arthur Sharpe home - too ill to work.

Jan 17th Sent Arthur Sharpe home with whooping cough.

Feb 2nd. Sent a note to parents of Joseph and Arthur Sharpe respecting arrears of school fees to the amount of 6s 3d.

(Later one boy left school 2/9 in arrears with school fees.)

Alfred Robinson who has been a stipendiary monitor (pupil teacher?) for 3 years left having obtained a situation as clerk under the Midland Railway.

Standard VI doing Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

“It is with deep regret that I have to report the deaths of two of my scholars through drowning. Viz; Joseph Cawthorn aged 9 and Charles Rostron aged 12. The latter lost his life in trying to save the former.

Mr Orford had to report at least two other deaths: George Lee ( in the Infant class ) died in January, and Louis Walker aged 5 died in October.

Letter from parents of Thomas Maddox requesting no home lessons because his Dr says he has irritable brain.

Poor attendance. Sent to about a dozen parents to know the reason - Washing day.

Punishments:

Corporal punishment: for throwing snowballs, eating nuts in school, copying answers to sums, “being saucy”, truancy, lateness, swearing, going into the orchard, inattention, fighting

Detention: e.g. kept girls in ¼ hour and boys ¾ hour for being noisy and inattentive.

Sometimes parents requested punishment “his mother asked me to punish him severely for bad conduct at home”

Nov 17th 1881 “Received from Mr Tatam the following resolution passed by the Board on Aug 27th” That until further notice the Schoolmaster and Schoolmistress be strictly prohibited from administering any corporal punishment whatever” - (nearly a century ahead of its time! adhered to for several months then abandoned)

June 14th 1885 “Having punished Nenian Thompson for talking during school hours, he in his hasty temper endeavoured to strike me with the edge of his slate, but did not succeed. I chastised him severely for so doing, and afterwards pointed out to him what the consequences of his ungovernable temper may lead to”

Aug 31st 1886 Ernest Fox slept in the toilets last night. He has a stepmother who treats him very harshly.

The following year 1887: “Trial of Mrs Fox March 18th. On charge of cruelty. I was absent in order to attend as a witness. She was convicted”

June 28th “No truancy for 6 years”

5. The School Board and establishing the new school 1880s

By 1880, It had become apparent to many people in the village that the school provision in Little Eaton was not good enough. There had been national legislation (the Education Act 1870) establishing School Boards for all parishes and boroughs across the country; and to make education compulsory for children between the ages of 5 and 10.

A School Board for Little Eaton was elected in 1880. Newspaper reports of the time report a good turnout and successful candidates, including Mr Cadlip, Mr Smith and Mr Tatham who undertook “to do their utmost to serve the ratepayers”.

The first Chairman was John Tempest. He objected to the cost of providing a new school and resigned (he died in 1882). He was followed as chair by Mr Birkinshaw and then by John Wykes who was a lawyer, lived at the Stone House and owned property in the village. The Board decided to build the new school on Alfreton Road and tenders were issued. But there was then a bitter row about how the tenders were dealt with. 1883 newspaper reports “difficulties arising out of the present attitude and composition of the School Board”. Mr Smith and Mr Mason resigned and laid a motion to remove the Chair, Mr Wykes. Mr Wykes wrote to newspapers to justify his decisions, but then resigned.

By the mid 1880s the Board had settled down. Its Chairman was Colonel Noel of The Outwoods and Vice Chairman was John Hastie of Park Farm. Other members included John Tatham of Elms Farm, T Pratt, the village grocer, George Thums, the village butcher and farmer of Church Farm, J Hill and Richard Poole (Chairman of the Parish Council).

G.T Terry was the Clerk. John Hastie and Richard Poole both had daughters teaching at the school.

The eventual cost of the new school was £1,800. It was decided that it should have a “Male Principal, and a certified teacher, assisted by 2 ex-pupil teachers and 2 pupil teachers.” It was opened on August 4th 1884 with Mr Orford as Headteacher.

The Board decided to enlarge the school almost as soon as it was built. In 1885, an Inspector recommended that there should be a urinal for the infant boys. In 1886 and 1896 there were significant extensions, including the addition of the clock, designed by Percy Currey, the well-known Little Eaton architect, installed as part of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

By 1912, there was an average attendance of 144, up from 120 in 1886.

(There were no further permanent extensions to the school until the present infant block was built in 2004).

Thomas Michael Walters was chairman of the School Board for 30 years, until his death in 1921. He had been a railway clerk and lived at The Grove with his wife and 5 children. In 1888, he chaired a board meeting when he reduced the summer holidays from 3 weeks to 2 weeks, and reduced the salary of the headteacher by £20 to £50 per year.

17 years later the Headteacher at the time (Mr Grocock) married Mr Walters’ daughter, Elizabeth Mary. He and his two children from his first marriage moved into The Grove with his new father-in-law. Mr Walters died in 1921. The Grococks continued to live at The Grove until Mr Grocock died in 1926. They had 4 children.

There were several advertisements, in 1891, 1900, 1911, 1923 etc for the sale by auction of The Grove, which was a very large imposing property with several acres of land. Mr Grocock died there in 1926 and the property wasn’t finally sold till after his death.

6. Headteachers and teachers from 1884 to 1952

Here is a list of Headteachers at the Alfreton Road school:

• 1884 to 1891: Edwin Orford (who had already been Head at the old school for 5 years)

• 1891 to 1892: Arthur Pritchard (who became ill and left to return to Coventry)

• 1892 to 1927: William Grocock

• 1927 to 1952: Arthur H. Hallett

Notable teachers:

• 1881 to 1926: Eva Green

• 1881 to 1901: Edith Poole

• 1891 to 1901: Elizabeth Hastie (Pupil teacher aged 16 in 1889)

• 1901 to 1920: Alice Tomlinson

• 1909 to 1922: Lizzie Fogarty

• 1907 to 1947: Frances Rhodes

Edith Poole, Eva Green, Emmeline Piggs and Miss Thompson

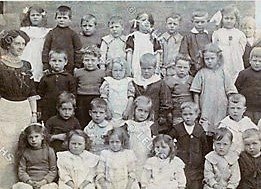

1895: picture of 74 pupils at the school plus the Headteacher William Grocock and teacher Eva Green.

William Grocock

William Henry Grocock was born in 1866 in Coventry. His father was a carpenter. He came to Little Eaton in his early 20s with Arthur Pritchard, another teacher from Coventry. These two boarded with the Ryleys on Alfreton Road. They both taught at the school. Pritchard was appointed Headteacher, but only stayed one year before going back to be a head in Coventry. Mr Grocock took over the headship in 1892, aged 25. The same year he married Annie Abbots. They had two children, Marjorie and Harry. Both the children went to Little Eaton School. Marjorie became a Pupil teacher by the time she was 16.

Mr Grocock stayed as headteacher for over 30 years to 1926. His wife Annie died, and in 1905 he married Elizabeth Walters, daughter of the Chair of the School Board. He and his two children moved to The Grove, home of the Walters family, and lived with his Chair of the Board, recently widowed.

He and his new wife had four more children: Frances Mary Grocock b 1906, Winifred Mabel Grocock b.1907, Anne Crawford Grocock b.1910, Arthur C.Grocock b 1912. Marjorie Grocock remained a teacher until she married in 1922 (Herbert Edgar Bowmer) at St Pauls. She died 1970. Anne Crawford Grocock became a teacher. In 1939 she was still teaching, living in Belper with her incapacitated Mother (widow) and sister Winifred, single and brother Arthur, single. She died in 1991.

Eva Mary Green

Eva Green had started teaching aged 15 in 1881 as a pupil teacher in the Parish Room school. She remained at Little Eaton School until retirement in 1928 aged 62. She was the Infants’ teacher and taught most of the village children between 1880 and 1926, including many of her own relatives. In 1888, an inspector’s report said “the Infants class were carefully taught by Miss Green”. By about 1918 she was the Headmistress of the Infants’ School.

The Greens were a well-established Little Eaton family. Her mother was Caroline, who lived all her life at Woodside Cottage. When her mother died in 1911, aged 87. Eva’s lifelong friend, Isabella Hastie (from Park Farm) came to live with her and together they brought up David Green, Eva’s nephew whose mother had died in 1906.

When she resigned in May 1926 Mr P.H. Currey presented her with a cheque for £30 from the whole village. There were also gifts of a handbag and purse from the staff and pupils.

When she died in 1928, the Derby Daily Telegraph reported “Little Eaton’s loss” and gave a long list of attenders at her funeral. She left money in her Will to her friend Isabella Hastie and her nephew David Green.

7. School life in the early 1900s

Gwen Tatham, the daughter of Edith Poole, lived in the village all her life. In her recollections she wrote about starting in Miss Green’s class at the age of four and writing on slates. She travelled to school by walking along the old Gangway which stretched from the Post Office to the Clock House.

Most children walked to school, even the few who came from Breadsall or Coxbench, sometimes carrying their shoes so that they could arrive at school with clean shoes!

School life for teachers was hard. There were up to 50 children, covering three or four age groups, in every class, lined up in rows of desks in front of them. They would be taught for most of the time as a class, chanting their tables and texts together. The teacher would try to spot children who were not keeping up and give them some special attention and there were pupil teachers to help some of them. But, however good the teacher, some children would be bored and others would be left behind.

Little Eaton school concert 1900

Schoolroom in 1912. The original floor is still in place today

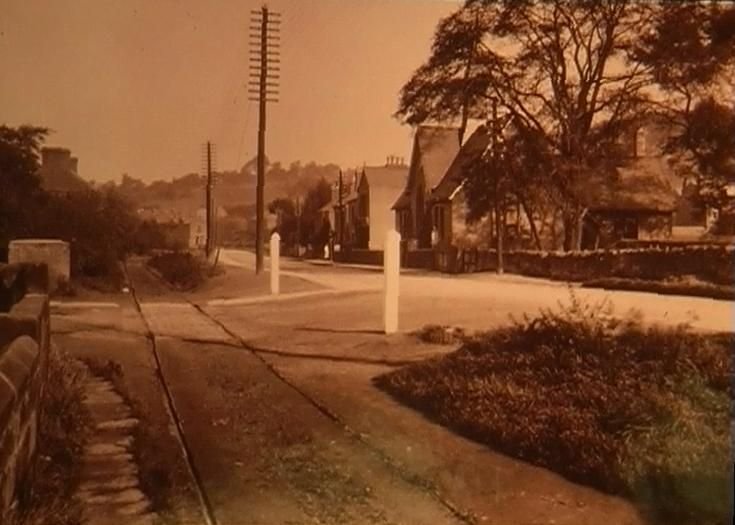

Road outside school, early 1900s showing tramway tracks

But it was not all work at school. A dance was held every Friday night in the school hall and there were plays and concerts put on at Christmas. Every year there would be a school trip with special charabancs and trains laid on. Sometimes the trips would be to Matlock but on occasion they would be as far away as Skegness, with many hours of travelling to get there and back.

Sickness was very common. A newspaper report from 1902 identified the dirty water in the brook as the cause and lamented that there was “nothing so effective as the loss of a horse in drawing one’s active attention to a defective stable door”.

1914: Miss Fogarty and Miss Rhodes classes

8. Between the wars: life at school

Mr Grocock was still Headteacher and was by then one of the senior Heads in the County. He became President of the Derby and District Teachers Association and his address to them is reported in the Derby telegraph in 1920. He talked about the need for reconstruction after the war: “There is nothing inherently greater, nothing more constructive or far-reaching, than the work of teaching”. He lamented the low pay and prestige of teachers and called for one professional association, representing all teachers: primary, secondary, technological, university.

Outdoor activity and exercise was important to Mr Grocock. School children dug the allotments behind the school (where terrapin classrooms were later built and the PlayQuest equipment stands today). This photograph from 1923 shows boys tending the vegetable patch with Mr Grocock the headmaster.

Mr Grocock was followed as Headteacher by Arthur Hallett. He had served in the first world war and been wounded. He taught the 11 to 14 year olds in a room with varnished mahogany boards listing the achievements of past pupils. He served as Headteacher until 1952, and was nicknamed “gaffer” by the children.

Our picture of school life between the wars comes mostly from the memories of Cathie Woodward. Cathie Woodward (nee Piggs) was born in 1924 with 3 older brothers and a younger sister. Cathie’s schooldays 1929-1938 were all spent under Mr Hallett as Headteacher. Her parents, her grandparents, her siblings, her own children and grandchildren attended the schools also. Her aunt Emmeline Piggs taught there until she died of diabetes aged 27.

Cathie remembered another teacher dying in 1932 – Grace Hillier, and also remembered a 5-year-old being killed on the road outside school. Another pupil who died just before Cathie left school was an 11-year-old who’d just passed the 11+ but died of meningitis before starting at the grammar school.

Cathie’s older brothers told how Mr Grocock and the top class had gone to plant 6 lime saplings on the bank between the Park and Church. She also remembered being told by her grandparents of the early Dames’ School where pupils were charged 1/4d a week ie: a farthing, and of the cholera epidemic of 1841.

Cathie remembers her first day at school; “Mother came with me for first and only time”. She remembers a handkerchief tucked into her bloomers, the smell of chalk, bad breath, unopened windows, hard smell of ink, cleaning resin.

Miss Potts, the Infant teacher, smelt of Coty talcum powder, mixed with chalk. The school was “not unlike a Convent”. Boys and girls were segregated - two entrances, corridors, cloakrooms but taught together in classrooms. Earth closets - boys and girls in same block, the teachers’ lavatory block next to the childrens’.

A bell called them to school and there were no excuses for being late. If anyone was one minute late for roll call they had to wait for headmaster in corridor. In the Infants’ room was a blazing fire, and Cathie remembered the children singing the alphabet and counting dots on the blackboard.

When she was in Standard 2, her teacher was Mrs Rhodes. Mrs Rhodes had no College education but was an excellent, well-liked teacher with firm discipline. She had “the gift of the gab” so her nickname was “Twitter”. Nicknames were common “Tarzan” being the nickname for Miss Baldwin, Cathie’s teacher when she was 9. In this class the curriculum included:

240 pence in the pound, inches, yards, chains, furlongs, gills drams ounces etc. (Children 10, 20 years later were taught the same things). Other memories were of learning poetry by heart, and practising for the dreaded scholarship exam.

Floods were almost a yearly occurrence. Teachers and children struggled through to reach school. The flood in 1932 was the worst. Children were given time off school as classrooms were under water. Cathie remembered how cold it was in the winters, with fires in the classrooms to keep them warm.

Flood at the school in 1932

Mrs Rhodes taught at the school for 40 years, before retirement in 1947. A school inspector once reported that too many teachers were too old, had been there too long and should be replaced by new blood.

“Every year we had a day trip to Skegness or Southport, organised by the Co-op Guild with Mrs Rhodes as leader”. (This day trip to Skegness is first mentioned in the log books in 1884)

Mr Robson taught the 10-year-olds then Mr Hallett took the older children with 40 pupils aged 11 to 14 – those who hadn’t passed the scholarship. The scholarship (or 11+) started in 1920.

At the age of eleven, children who could pass the entrance exam went to Grammar school. Special buses took more than 40 children to Strutts, Parkfield Cedars and Bemrose Grammar Schools. Some Grammar school places could be bought by richer parents who could afford fees. Clever “arty ones” went to Green Lane Art College at the age of 12. The rest stayed on at Little Eaton.

Cathie left school in 1937 to work in Derby. Other leavers that year went to the Mills, to Rolls Royce, Engineering firms, as Miners, the Railway or the Army.

9. The War Years

During the war years, life in the school reflected the world outside. Shelters were built in case of bombing and children were issued with gas masks and shown how to use them. Details of measures to be taken at the school in the event of air raids during school hours were issued and air raid practices were undertaken. The conversion of one of the school’s main corridors into an efficient shelter was considered by the managers. Children knitted over 300 squares to make into blankets for the Red Cross.

But the day-to-day life of the school continued. In 1942, there was a village petition to the County Director of Education calling for school meals to be available for children at mid-day. The curriculum and teaching practices carried on as before. Occasionally there was a stark reminder of the war. There was bombing in Derby and children would be aware of the danger to their parents and elder siblings.

The picture shows soldiers marching past the school during the Second World War. Note the kitchen extension now covering the side arch window of the hall.

It is not known how many of these soldiers came from Little Eaton or would later have their names inscribed on Little Eaton’s war memorial.

10. Post war to the present day

The post-war Headteachers were:

· 1927 to 1952: Arthur Hallett

· 1952 to 1959: Robert Elliot

· 1959 to 1970: Harry Taylor

· 1970 to 1986: David Paling

· 1986 to 2008: Phil Howard

· 2008 to 2019: Richard Bateman

· Present: Paul Schuman

1944 Education Act

In 1944, there was “The Butler Act”, a major reform of the education system in England and Wales. The Act absorbed Church schools into the state system in return for funding. It ended 5-14 schools and divided education into Primary schools (to age 11) and Secondary schools (11+). It abolished fees for state secondary schools. It created three types of secondary school: grammar schools for the academically inclined children, technical schools for technical tuition and secondary modern school for the rest. The “11 plus” exam would decide which children went to which type of school. There was a new system for setting teacher salaries and a new duty to provide school meals and milk

Those aged 11+ would either go to grammar school at Belper, Spondon Park or Derby, or to the secondary modern school or technical school in Denby. But nothing happened until the late 1940s. In 1948, those aged 11 to 13 were still at Little Eaton and did not attend the Denby Smithy Lane Secondary Modern until aged 13.

Then different patterns of school attendance emerged with grammar school children mostly going to the Strutt school in Belper, secondary modern children going to Breadsall or Allestree and technically inclined children going into Derby.

A new school site?

For Little Eaton, it was proposed in 1947 that there should be a new Primary School on a new site. A 3- acre site had been set aside in Barley Close for playing fields, 4 classrooms, and a nursery.

In 1949 Little Eaton school was still on the same site and had only 4 teachers for 180 pupils. The proposed new school never happened.

By the 1960s there were yet more plans and in 1984 an Action Committee was formed to try and stimulate some progress. There was still overcrowding and 20 pupils had to have their lessons in the OAP Hall.

Other issues

School PE lesson in 1956

Other issues occupied the minds of teachers, managers and parents. Accidents seemed frequent. A newspaper article December 1945: Mrs E.D. Tibbles headed a petition to the Parish Council, requesting a policeman be on duty when the children came out of school – her five- year-old daughter Anne was knocked down by a bus and had a fractured skull. In those days, parents did not take their children to school and Anne went to and from school on her own - her mother told the newspaper: “I would take her myself but I have a 3 year old to look after”.

Mrs Gregory was appointed as traffic warden 1968 but resigned only weeks later as she became very anxious and nervous of the heavy traffic. The crossing remained unmanned until November when Mrs Lawbourn volunteered to do it. There continued to be accidents until 1975 when the pelican crossing was built in January 1976.

There was frequent flooding of cellars. The school was flooded four times between November 1963 and January 1964 with damage to the school. There were debates about school meals and school milk – particularly when Mrs Thatcher stopped milk in 1972.

Swimming lessons had started in 1948 but were often cancelled when buses didn’t arrive. Teacher recruitment remained a problem, and there were debates about infestation of nits in 1966 and mice in 1968 and about chickenpox and flu.

School paper collection in 1974

School standards

There was constant debate about standards and much concern about apparently low rates of success in the 11 plus exam. In the 1950s, a row erupted over school standards, as there were poor results throughout the 1950s. Only 4 children passed the exam in 1951 and 1952, only 2 passed in 1953, 1954 and 1955, only 1 passed in 1956, 5 passed in 1957, and 4 passed in 1958. 0nly 1 passed in 1959. John Easter, chairman of the managers demanded action.

The 11 plus exam was finally abandoned in 1976 and the present comprehensive system introduced. Most children go on to Ecclesbourne; a few go to other schools in Allestree, Derby and Denby.

1980 to 2020

The 80s, 90s, and 2000s have seen four headteachers (Mr Paling, Mr Howard, Mr Bateman and Mr Schumann) develop the school together with a committed and dedicated staff team.

Janet Easter was a familiar face welcoming children, staff and families as school secretary from 1975 to 2006. There were many others who stayed for more than 30 years including Sheila Gascoigne and Andrea Wilson.

In 2004, the overcrowding was finally eased when Glenda Harrison and her family sold some land to the Council to build the new Infant block and playground. This meant that two of the temporary classrooms could finally be demolished and the school hall no longer had to be used as a classroom. Four bright new purpose-built classrooms, shared space and a new playground were built. The picture below shows

Phil Howard, the Headteacher at the time, onsite with the builders and (below the children celebrating the opening of the new block. )

The school now is thriving. It has 210 pupils and is staffed by a Headteacher and seven class teachers, with 22 other staff assisting in the classroom, supervising meals, managing administrative work, coaching, or looking after the building. It has a supportive governing body and parent teachers’ association. It is classed by Ofsted as “good”. Its future is secure and will serve the village well for future generations.

Comments

We know that many people reading this article will have attended or worked at the school and have memories and photographs that we can add to the site.

Your memories and stories of the school can be added to the history for future generations.

Clare Howard, Philip and Ruth Hunter

Sources: Cathie Woodward: A Native’s Tale: Memories of Little Eaton;

Colin Stevens: Caroline (see website); Peter Lyne and C Shepherd: Little Town By the Water.