The Canal and Gangway

The Little Eaton Canal: 1795 to the present day

Painting, hanging inside the Clock House

Construction of the canal, gangway and Clock House

The Derby canal

The Derby Canal was first advocated by James Brindley in 1771 as the transport system in the town was poor, coal was expensive, the roads were inadequate and the river Derwent was prone to flooding. Twenty years later, in September 1791, a meeting was held by a committee of businessmen at Bell Inn in Derby to discuss the cutting of a canal – several such meetings were held, and the committee commissioned Benjamin Outram to survey and estimate for a broad canal to run from Swarkestone to Denby in the Bottle Brook Valley north of Derby, with a branch to Sandiacre on the Erewash Canal. Because of the high cost which would have been involved in cutting the steeply graded section from Little Eaton to Denby, it was decided that this northern part should be a tramroad up to the Denby collieries.

The cost of the construction was £60,000 and this sum was to be raised by the issue of 600 shares of £100 each, floated in 1793. Francis Radford and Thomas Tempest of Little Eaton were amongst the purchasers. The cost of building the canal in today’s money is around £60 million.

This plan was accepted and the petition to parliament was presented on the 2nd of February, 1793, with Royal Assent being given on the 7th of May, 1793. The canal mainly carried coal (as had been planned) but it also carried stone, corn and cement.

View a simulation below of Little Eaton branch of the canal.

The Clock House

The Clock House was built in 1795 by the Derby Canal Company to house the canal agents and their families. For almost 150 years it was one of Little Eaton’s most iconic buildings, standing prominently at the head of the canal, acting as the villagers’ timepiece and becoming home to scores of families who worked on the canal, the railway, the mills and the quarries.

The Gangway and wagons

The Little Eaton Gangway, or tramroad, ran from the end of the canal in Little Eaton to the collieries at Denby. Under the direction of Benjamin Outram, the gangway took two years to build from 1793 to 1795. Wagons loaded with coals were pulled by horses up and down the line, which was single track with passing places. The tramroad was laid with L-section, cast-iron rails, so that the wagon’s wheels fitted inside the rails, rather than the usual method used in railway tracks. The rails were 3 feet long and they weighed 28lb.

A unique feature of the tramroad was that the top of the wagons were detachable boxes, which were lifted from the wheelsets and placed directly in the waiting narrowboats, and when they arrived in Derby they were lifted out and placed on carts for haulage around the city – probably the first form of containerisation in the world. The wagons themselves hardly changed in over 100 years of use on the gangway. They were horse drawn and held 2 tons on coal each (48cwt).

The picture below shows a wagon thought to date from 1798, and clearly shows the flange on the rail rather than on the wheels. The main axle was made of oak, cheaper than wrought iron, and it carried iron stub axles.

Tramroad with detachable box

The gangway itself became a feature of the village, with horses and wagons travelling up from the canal, behind the Queen’s Head, along what is now Alfreton Road, under Jack O’Darley’s bridge and on to Denby. The two pictures below show the gangway under the bridge, then and now.

The first coals are delivered

On completion of the Little Eaton line of the canal and the tramroad, the first coals were delivered to Derby in May 1795. It took three hours for the coal to travel the four miles from Little Eaton to Derby. William Drury Lowe, the owner of the pits at Denby, ordered that the first boatload of coal be distributed for the benefit of the poor.

The Canal Agent

The role of Canal Agent was a prestigious position and the terms and conditions were generous, signifying the importance of the role: a salary of £40 per annum, plus the occupancy of the Clock House and the garden. By 1841, the salary had risen to £80 per annum.

The duties of the Agent included a general responsibility for the maintenance of the tramroad. The Canal Company ordered that the Agent was to:

"go up the Railway to Smithy House at least three times every week to examine the state of the railway and to keep the labourers to their work and that he write down his observations thereon in a book to be kept for the purpose and to send the same to the Committee previously to every meeting"

Life on the Canal: the boatmen

A snapshot of the life of work on the canal is given by Mr J Titterton of Derby, describing his time working on the boats from age 14 to 16 in 1906-1908.

“Denby Colliery sent 2-ton boxes of coal on the lines to Little Eaton. Four horses used to bring six 2-ton boxes each time. They used to lift these boxes, six in each boat, facing the New Inn Public House, all by hand crane. The journey to Derby used to take 2 hours to go and 2 hours to come back and 2 hours to unload.” The journey was reported as three hours long when the canal opened, so one hundred years of progress had led to shortening the journey by one hour.

Although the work must have been hard, it was not always monotonous as coal was not the only thing transported – the Derby Mercury reported on 19 April 1826 that a llama, a kangaroo, a ram with four horns and a female goat with 2 kids arrived in Derby via the canal!

Wages of the boatmen at this time were 3s 8d per trip for men and 3s 4d per trip for boys. Unlike more respected professions such as those in the colliery or the quarries, those that worked permanently on canal boats were viewed with disdain by the Victorians. Canal People drifted apart from land locked 18th and 19th century Britain, developing their own free-floating canal culture, traditions, customs, ways of work and dress. They lived in a closed community. Most boat people were born and brought up on the canals and they tended to marry other boat people. Few non boat people decided to work the canals.

The prejudice experienced by the boat people was demonstrated in a speech by Mr Johnson to a public meeting in the Guild Hall, Derby. Arguing for the canal to be replaced by a railway he said:

“I have always understood too that boatmen are the worst of neighbours, they are a nuisance wherever they set foot upon the land (hear, hear) – and if I recollect right – I have heard Mr Crewe himself complain of the depredations committed by the boatmen on this canal, and of the very unfavourable effect produced upon the inhabitants of the village, by contact with them; so that I think the conversion of the canal into a railway should be regarded as a benefit rather than otherwise.”

Life on the Canal and Gangway: the horses

Horses were the life blood of the Clock House, gangway and the canal. On the gangway, each horse pulled two wagons of two tons each (whereas the water on the canal allowed one horse to pull up to 50 tons alone).

The number of animals involved was enormous and the number of workmen needed to keep all this horseflesh shod, fed and healthy was equally large. Horses were stabled and fed all the way up the four mile stretch of the gangway from Little Eaton to Denby – each horse was fed well and regularly with corn, crushed oats and chopped hay.

Little Eaton horses would have been stabled at the Clock House, the Delvers Inn (or Queens Head as it was renamed), the New Inn, in stables behind the Kings Head on the Town, and in various places up the gangway to Denby. Larger establishments employed ostlers to look after the change horses and sick horses, and they would keep the stable mucked out and ready for use for their boating customers.

A horse could wear out a set of shoes in four to six weeks – the Little Eaton smithy was built alongside the gangway and still operates from the same building on Alfreton Road near the Queen’s Head.

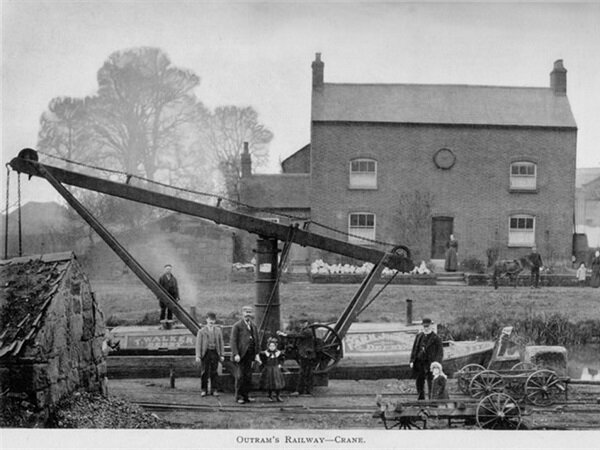

The picture below shows all aspects of the canal and gangway in front of the Clock House: the large crane used for lifting the wagon boxes onto the narrow boats, the horses, the wagon wheels remaining on the gangway, and the people who lived and worked at the Clock House.

The decline of the canal

Throughout the 1800s, the railways were to transform industrial Britain. In 1830 the Derby Canal Company commissioned George Stephenson to investigate the feasibility of converting the Little Eaton branch of the canal and the gangway into a railway, to fend off competition from the road and ensure that coal reached Derby more quickly. Stephenson estimated that the cost of the works would be around £13,000 and recommended that a new line be built, to allow transport to continue whilst the work took place. However, the Canal Company did not act on Stephenson’s recommendations, relying instead on short term increases in the price of coal and their profits.

The Canal Company’s failure to act on Stephenson’s recommendation was to prove fatal, as the Midland Railway was then extended from Derby to Little Eaton in 1848, and then extended further to Ripley by 1855. The colliery owners began to use the goods trains instead of the canal, and trade on the canal declined dramatically between 1860 and 1900.

In July 1908, after years of decline, the last load of coal was delivered along the gangway to the Clock House at Little Eaton. The photographs show the last gang of wagons to travel down the full length of the tramway, from Denby to Little Eaton, on the day of its closure.

Four years later, in October 1912, the Canal Company announced they were abandoning the canal as “the maintenance of it is now a great expense to the Company without any return”. By 1930, an article in the Derby Telegraph declared that the canal was “a white elephant” and should instead be converted into a “fine highway for fast motor traffic. Such an arrangement would relieve a busy and all too narrow main road”.

The Little Eaton branch of the canal was therefore filled in and is now the site of the A61 Sir Frank Whittle Road.

By Clare Howard

References and acknowledgements:

Caroline: Her Life in the Bluebell World of Little Eaton – Colin Stevens - Colby Stevens Moore

A Native’s Tale: Memories of Little Eaton – Cathie Woodward

The Little Eaton Gangway and Derby Canal – David Ripley